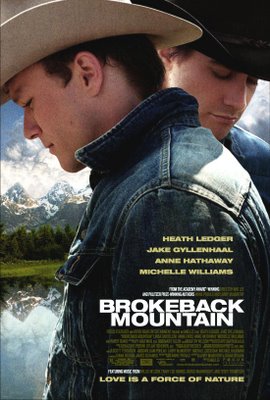

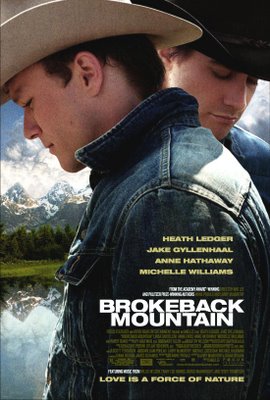

Brokeback Mountain (2005) (Ang Lee)

It’s easy to be superficial about a movie such as Brokeback Mountain, a film adapted by Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana from Annie Proulx’s 1997 short story. Its content draws mixed reactions from every generation and social strata, all carrying weighty and complex opinions. Branding this film as just another gay-themed movie that Hollywood churned out would be downright ignorant. Its final act forces us to consider that the backdrop of homophobia being unavoidable is as potent a notion as the film’s statement of unconditional love being unrealisable.

Although far from being a trailblazer in its controversial content, this is one of the most important love stories told for the past 3 decades, and refreshingly, it is not left to European arthouse cinema this time. This taboo topic was earlier breached in 1969’s acclaimed Midnight Cowboy with its original rating of X and 1992’s Oscar nominated The Crying Game that sparked a furore among censors and critics for its then shocking twist.

Fast forward to this year’s celebrated alternative cinema offerings such as Transamerica (winning Felicity Huff an Oscar nod), Breakfast on Pluto (Cillian Murphy, from Batman Begins was exceptional as a out-of-touch transvestite) and the underrated comedic film-noir, Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang. All will be screened in Singapore in the coming weeks, hot on the heels of the Oscars.

This movie defines the year’s cultural zeitgeist, a year riddled with polemising gay rights issues and the ensuing fallout of not being taken seriously enough. The majority of moviegoers deal with it by cracking jokes and nervous laughter while discussing the film’s merits, evident by America’s late-night comics using it as fodder in their tired comedy routines. It has galvanised the gay community so strongly that a movie critic, Gene Shalit was condemned by gay rights activists for referring to 1 of the main characters as a “sexual predator” during his review. Has any review of any other movies drawn such a fierce response for its assessment of a character?

Celluloid romances and rugged Western terrains complete with cowboys have never appealed to me, even as 2 separate genres. Although appreciative of both genres’ successes and appeal, I’ve always seen them as a byproduct of heightened cinematic sentimentality and gasconading bravado of its masculine characters. With Brokeback Mountain’s immense buzz and hyped up performances of its leads coupled with 8 Oscar nominations, I was inclined to think, before watching the film that its publicity machine was merely working overtime. I was wrong.

During the summer of 1963, 2 men discover their futures in Brokeback Mountain, Wyoming. It’s where they met and it’s where they found themselves. At the tender age of 19, Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger) and Jack Twist (Jake Gyllenhaal) are paired up by Joe Aguirre (Randy Quaid) to herd his sheep through Brokeback Mountain to market. It slowly starts as a friendship established on a mutual understanding of making their way through the hardships of their world, but somewhere along the way things became complicated. A cold rainy day forces the 2 cowboys to shack up in a single tent, which leads to the first unflinching expression of their attraction. As both cowpokes leave the mountain early, they ambivalently acknowledge their burgeoning affection for each other.

These first 30 minutes gave us the incredibly subtle courtship rituals between the 2 sheepherders as their attraction starts to simmer with the furtive glances while their macho swagger turns into amorous endearment. Even while we knew what was about to transpire, it is all the more important for us to realise why both men needed each other.

It was definitely an affair to remember, complete with the obligatory first full-fledged, if brief, sex scene, accompanied by several moments of ardent, soulful stares and a final self-sacrificing moment in which Jack drives away from the love of his life. Those well-wrought scenes built the foundation of the remaining film by arresting our attention to the untouchable desire Ennis and Jack feel during the long droughts in their romance.

The cowboy that initially reveals his advances first did not necessarily make it as clear-cut as we would have liked. It is often said that men have sex first, and then they fall in love later. The film keeps us wondering even on the way home or as we brush our teeth, about which of the 2 men fell in love first and what might have been if they had consolidated their relationship before they complicated it.

The film’s second act continues with the men moving on with their lives during the next 4 years by marrying wives (Michelle Williams and Anne Hathaway) and siring children. A fateful postcard from Jack sets off an illicit affair between them for the next 20 years under guises of fishing and business trips while their marriages and relationships with women falter and fail. Their preferred hideaway remains Brokeback Mountain.

The titular location is stupendously photographed, and its majestic panorama fits in well with director Ang Lee’s delicate tact in creating a gentle coupling of lonely spirits instead of a raunchy flaying of clothes and assembly of limbs. A singular guitar chord manages to invoke the sharp pang of hurt and empathy for the unrequited lovers each time another obstacle is thrown their way. Nothing is done just to simply elicit emotions as each action is presented as pure and unbridled. The interactions between the 2 leads are always sensitive, and never unnatural or overly sappy.

Compassionate and provocative over the bleak landscape of Wyoming (except that it’s really Canada) and the deafening sound of silence, Ennis and Jack treasure their solitude as much as they dread hiding themselves from the world. The idea of 2 lost souls connecting, exploring each other’s truths is common, yet its subtext is usually only explored on a physical level. However, with Lee’s interpretation of the 2 men’s initial ambivalence towards their feelings and resulting wrong turns while traversing through their sham lives is clearly evident through his 2 wholly convincing male leads.

Ennis is a closed-off, stoic rancher who’s torn between the love of his life and his idea of continuing traditional romances with different woman to avoid acknowledging his homosexuality. Ledger is note perfect as he delivers a thoughtful and true performance in each scene. He hermetically seals himself in his character’s turmoil by giving an incredibly nuanced portrayal of a torn human being. It stays remarkably restrained and through his implicit reactions, shows the true introvert Ennis is, even as the closet gets too small for him to hide in.

With a runtime of just over 2 hours, the movie will start to nag at and bore through those that didn’t start watching it with an open mind. Its patient and deliberate pacing involves us at every juncture, but its apex lies in its rapturous opening scenes and its scenes set in Brokeback with Ennis and Jack. Nothing else in the movie manages to approach its untainted exploration of each cowboy’s emotional states when they are together. Perhaps that’s the film’s sole limitation when it fails to transcend the inescapability of both men’s magnetising screen presence or maybe it’s the film’s strongest aspect as we’re drawn to their devotion to each other while constantly peppering us with the realisation of a possible unhappy ending.

It’s a story about the cowboys’ future, not their past as we hardly get a glimpse of their lives before that fateful day at Joe’s except for references of childhood experiences. We follow them through their tumultuous marriages and the self-destructive decisions they make. Their romance becomes a quicksand that they struggle in as they consider their homosexual relationship for the rest of their lives. It pulls no punches, literally, as their onscreen romance plays out as real and ugly as the emotions they feel.

The women in their lives play an auxiliary part, plastering over the cracks in the men’s agonised souls. Their love for the men may have been transient but not the impact they had in their husbands’ lives. Williams gives her all in her role as the long-suffering wife of Ennis. In a tableaux set in a kitchen, she fires off her frustrations in an intense scene that all but seals her Oscar nomination and puts her as the front-runner at this year’s awards.

Both Ennis and Jack are 2 of the most memorable characters in cinema this year. While it’s lauded as one of the greatest love stories ever told, its distinctive gay themed romance is made even more laudable when it stretches beyond our intrinsic societal boundaries and tremblingly touches our hearts with its unifying resonance.

Rating: 4 ½ out of 5